THE LITTLE FALLS CANAL

A Restoration and Education Project of the

New York State Museum

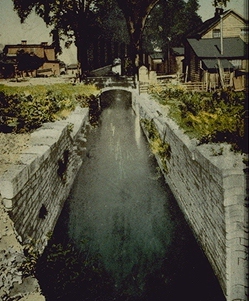

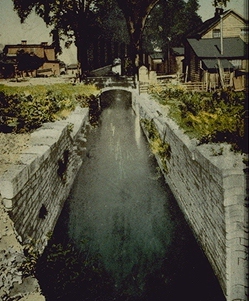

Guard lock, Little Falls Canal, as rebuilt in 1803. New York State Museum. Used with permission. |

Since prehistoric times, the Mohawk/Oneida waterway corridor has provided a passageway through

the mountains that separated the Atlantic seaboard from the Great Lakes. In 1796, when the

Connecticut Land Company survey teams shipped out for the Western Reserve, they passed along this

water route and must have been glad to find the first of what was to be a long series of improvements:

a canal around the "Little Falls." The process of broadening this channel and easing the passage from

the Hudson River to Lake Erie would culminate thirty years later, in the great Erie Canal.

The following article was adapted from a brochure prepared by the New York State Museum to commemorate

the bicentennial of the opening of the Little Falls Canal - 1795-1995. It is reprinted by permission of The

University of the State of New York/ The State Education Department. |

In a time when roads were little more than dirt paths cut through the wilderness, easily

turned into quagmires by melting snow or a sudden shower, these waterways represented the only

reasonable means of transportation.

Throughout the 1700s, the rivers, lakes, and streams that connected the Upper Hudson River port at

Albany with the Great Lakes landing at Oswego, served as avenues of international conflict and war.

The British and French, and later British and Americans, struggled with each other to control this inland

route.

But after the Revolutionary War, as settlement expanded into areas that were once again secure, the

same waterways that had provided access to the interior for soldiers and explorers now served the

peaceful pursuits of settlers and merchants.

The Mohawk/Oneida waterway was a transport corridor of national significance in the decades

immediately after the war. Other than the St. Lawrence River, which remained under British control, it

continued to be the only feasible means of access to the Great Lakes region for the emerging nation.

With the establishment of new settlements along the frontier, and to accommodate the greatly

increased commercial demands of merchants anxious to supply these new farmers with goods exchanged

for their agricultural produce, it was necessary to facilitate westward expansion by improving

transportation.

Onto this scene came retired Revolutionary War hero Philip Schuyler, of Albany, who was

instrumental in establishing New York's first canal company, 25 years before the Erie Canal.

Established by the State Legislature in March of 1792, the Western Inland Lock Navigation

Company over which General Schuyler presided was charged with the improvement of the natural

inland navigation route that connected Albany with Oswego.

To follow this transport corridor west in that time, one first went overland from Albany through

sixteen miles of dismal pine barrens to the Mohawk River harbor at Schenectady, thus avoiding the

Great Cohoes Falls.

From this small port, boats could be navigated to Fort Stanwix [now Rome] at the head of the

Mohawk navigation. There were almost one hundred rapids or "rifts" to be passed in the river, many

less than knee-deep. It was the shallowness of the water, rather than the violence of the current, that

frustrated boatmen.

At Fort Stanwix a land portage forced boats and cargo to be carried overland two miles to Wood

Creek, which flowed down to Oneida Lake. Crossing that lake brought one to the Oneida River, then

the Oswego River, and finally, nine or ten days after leaving Albany, to the Great Lakes harbor at

Oswego, on Lake Ontario.

Even with their light, flat-bottomed batteaux, navigators often found the trip intolerable. In the dry

season, rifts with only inches of water prevented the passage of fully loaded boats. Running half-loaded

boats reduced the profitability of the trip and delayed the transport of goods and produce.

Even in periods of deep water, a major obstacle to the Mohawk River leg of the journey existed at

Little Falls, so-called in relation to the Great Falls at Cohoes. Here a thundering rapid cascaded down a

river bed full of boulders, dropping forty feet in just a mile.

Boats had to be unloaded and dragged around "The Falls" on carts, with the added expense and delay

such a portage imposed on inland shipping. So it was to this place General Schuyler's canal company first

turned its attention. And it was here, beside this rocky chasm, that the first true canal for navigation in

New York State was begun in 1793.

Canal building was virtually unknown in New York State in 1793, and rarely contemplated anywhere

else in America at that time. In fact it was not until that year that British canal building really began to

take hold, although there had been canal projects in England and Europe for many decades.

Since American civil engineering was still in its infancy, General Schuyler relied on the expertise of

millwrights and carpenters for opinions on how best to surmount the falls and bedrock outcrops of Little

Falls, and for a time he served as his own chief engineer.

To raise and lower river boats over the forty feet that separated the upper and lower landings at

"The Falls," Shuyler's contractors had to use black powder to blast through over 2,000 feet of extremely

hard bedrock.

But although the cut created by this blasting was in solid rock, the one guard lock and five lift locks

required were made of wood, with their timber joints filled and caulked like the seams of a ship to

prevent the water in the canal from leaking out.

In some locations a massive earthen embankment was created to carry the canal across level ground.

By 1800, the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company had cleared rivers and streams of rocks

and driftwood all along the inland route, constructed stone dams to raise water levels on some of the rifts,

and had built three short canals at Little Falls, Rome, and Fort Herkimer.

The Little Falls Canal passed its first batteaux through on November 17, 1795. Although barely a

mile long, its five locks and dramatic lift of over 40 feet made it truly one of the engineering wonders

of its time. That boats could now pass all the way to Rome without unloading was a major breakthrough

in inland transportation.

But the canal was not without its problems. The wooden locks soon began leaking, and within a few

years were starting to rot. The massive embankments that held the canal along the elevated terrace

needed constant attention to prevent water spilling out through their poorly built walls.

So in 1803, as part of a general rehabilitation of many of its works, the Western Inland Lock

Navigation Company reconstructed the locks of the Little Falls canal with stone from a nearby quarry

and mortar made on the spot.

This canal served for another twenty years as a strategic part of the inland navigation corridor

created by General Schuyler. By combining improved natural waterways with new, artificial

constructions, such as these short canals, he was able to connect Schenectady and the western

waterways leading to Lake Ontario with one, continuous channel.

This eliminated the troublesome portages and made possible the introduction of the large river

freighters called "Durham boats." These craft came into general use in the last decade before the

opening of the Erie Canal in 1825.

The western half of the Little Falls Canal continued to serve as a feeder to the Erie Canal during the

nineteenth century, supplying water and passing boats over the historic aqueduct that spanned the river.

The eastern half of the canal slowly disappeared under urban fill.

Since construction of the Barge Canal in the early twentieth century would make this feeder obsolete,

the State of New York turned over the western end of the old canal to the City of Little Falls in 1883 as

an historic preserve. Remnants of the guard lock here, as rebuilt in 1803, can still be seen.

HOME